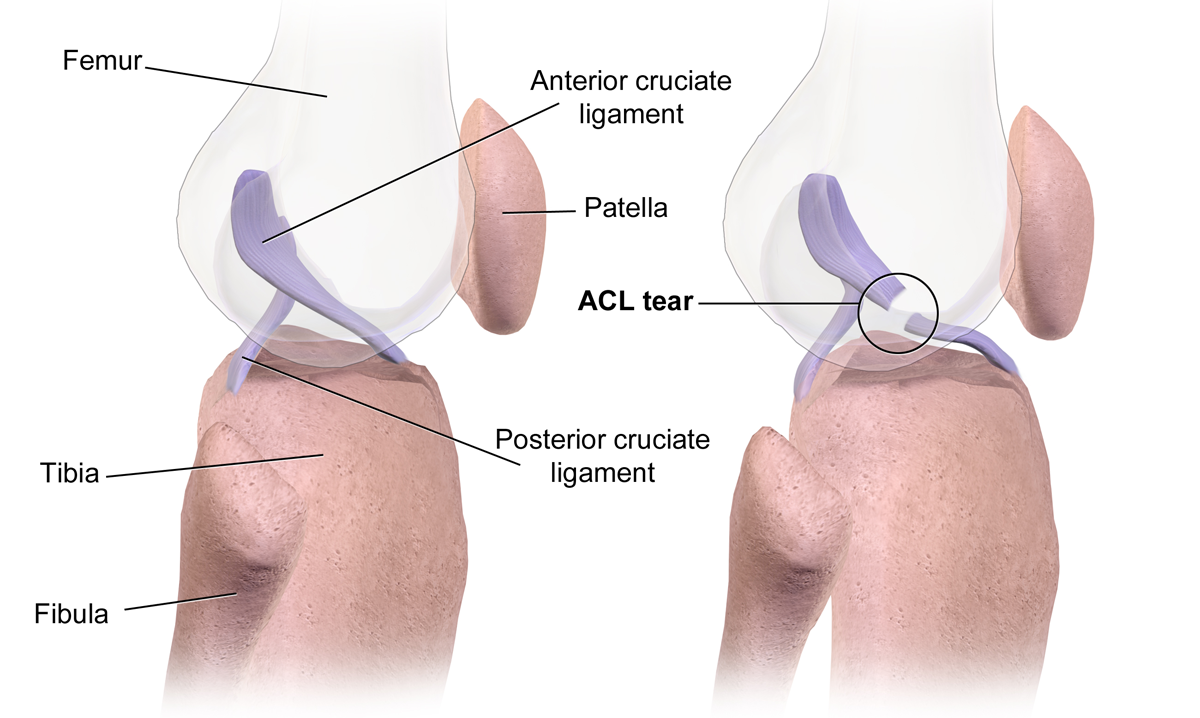

Anatomy of an ACL tear

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most important stabilizers of the knee. It connects the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone) and plays a vital role in controlling how the knee moves. Its main job is to prevent the tibia from sliding too far forward and to help prevent knee hyperextension and excessive rotation, especially during sudden movements like pivoting or cutting¹. Roughly 85–90% of the knee’s passive anterior stability is provided by the ACL.² When it tears, the body loses its primary stabilizer, making the knee unstable during high-speed or change-of-direction movements.

Other tissues that work closely with the ACL include the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the menisci (shock absorbers), and the joint capsule. The hamstrings and quadriceps muscles also assist the ACL dynamically by controlling knee motion during movement. When an ACL tear occurs, it’s not uncommon for additional structures, like the meniscus or MCL, to be damaged as well, which can significantly impact both recovery time and long-term knee health.³

Tearing the ACL is a potentially devastating injury for athletes. While ACL surgery has come a long way, studies show that only about 55–65% of athletes return to their prior level of performance after reconstruction.¹

Cause of injury

Approximately 72–78% of ACL tears in athletes are due to non-contact injuries, while the remaining 22–28% involve direct contact.¹² Non-contact ACL injuries typically occur during cutting, pivoting, or deceleration movements, often without any collision. These injuries often happen when the athlete plants the foot and the knee collapses inward (knee valgus), while the body rotates in the opposite direction. This combination of forces creates excessive torque across the ACL, especially when the athlete’s weight is moving forward. Fatigue, weak hip/core stabilizers, poor landing mechanics, and limited ankle mobility can all contribute to this chain of events.⁴ This was seen in Odell Beckham Jr. during the 2022 Super Bowl, when he re-tore his ACL while running a route and attempting to stop and turn. Non-contact tears are more common in skill-position players like wide receivers and defensive backs due to frequent rapid acceleration and changes of direction.⁵

The remaining 22-28% of ACL tears occur from direct contact with the knee.1,2 Contact-related ACL injuries, while less common, typically involve a force applied directly to the outside or front of the knee while the foot is planted. A clear example is J.K. Dobbins’ ACL tear in 2021, when a defender’s shoulder struck his knee, forcing it into hyperextension with valgus collapse, a combination of inward buckling and over-straightening that can rupture not just the ACL, but other tissues as well. These high-energy collisions often result in combined injuries, such as ACL + MCL tears, bone bruises, or meniscal damage.⁶ The type and direction of the force determine the additional tissues at risk. For instance, contact from the lateral side often injures the MCL and medial meniscus in addition to the ACL. In 2024, we saw Brandon Aiyuk tear both his ACL and MCL from a contact injury when his right foot was planted and his body weight was moving forward and to his right, and the defender hit his knee going the opposite direction.

ACL tear surgical reconstruction procedure

There are several options for surgery after an ACL tear. Most procedures today involve reconstructing the torn ligament using a graft, usually taken from the quadriceps tendon, hamstring tendon, or patellar tendon. These are small portions of tissue harvested from the patient’s own knee to rebuild the torn ACL. Unfortunately, using a graft from the same knee can cause temporary weakness in the harvested muscle group, making early rehab more challenging. You may be asking, “Why not use tissue from the other leg?” or “Why not use something artificial?” Grafts can come from:

Synthetic grafts (e.g., Gore-Tex): Largely phased out due to poor long-term outcomes

The injured knee (autograft): Most common

The uninjured knee (contralateral autograft): Rare due to the risk to the healthy leg

A cadaver (allograft): Is often used in older or non-elite athletes

Among autografts, patellar tendon and quadriceps tendon grafts tend to offer better knee stability and lower re-tear rates in high-level athletes compared to hamstring tendon grafts.⁷ Patellar tendon grafts have the lowest failure rate (~2–5%) but are more likely to cause anterior knee pain. Hamstring grafts are less painful but carry a slightly higher re-tear risk (~6–9%), especially in younger athletes.⁸. Cadaver grafts (allografts), though appealing due to less initial pain, are associated with significantly higher failure rates in young and active athletes, often 2–3 times higher than autografts.⁹

During surgery, the patient is placed under anesthesia and positioned face-up. The surgeon removes the damaged ACL, then drills two small bone tunnels — one in the femur and one in the tibia, to anchor the graft. The tendon graft is then threaded through these tunnels and fixed in place using screws or buttons. In some advanced techniques, surgeons use internal bracing or double-bundle reconstructions to more closely replicate the native ACL’s anatomy and biomechanics.¹⁰. Once secure, the new graft becomes a scaffold that the body uses to regenerate ligament tissue over time, a process called ligamentization. A critical part of the procedure is ensuring correct graft tension and placement, as small differences can lead to poor knee stability or early failure.

ACL tear surgical reconstruction outcomes

In the past, an ACL tear was a career-ending injury. Fortunately, modern surgical techniques and advanced rehab protocols have changed that. Today, research shows that approximately 87.8% of NFL players return to their previous level of participation following ACL reconstruction.³. However, success isn’t universal. Even in elite athletes, there’s an approximate 13% risk of ACL re-tear (to either the same or opposite knee) after surgery.³ Offensive players and younger athletes tend to have more favorable outcomes, while older players and defenders are more prone to complications and career decline.

In a study published in 2022, researchers looked at 312 NFL players who suffered ACL injuries between 2013–2018. Only 55.8% returned to play, and just 28.5% remained in the league three years later⁴. Several newer studies reinforce that return-to-play (RTP) rates are heavily dependent on position. Quarterbacks have the highest RTP and lowest performance drop-off, wide receivers and running backs show the greatest risk of re-injury and post-injury performance decline, and defensive players return less frequently and often play fewer snaps or experience contract delays⁴⁻⁶

A 2023 NFL-specific study found that players who returned to play before 10 months after ACL reconstruction were 2.3 times more likely to suffer a second ACL tear (either the same or opposite knee) compared to those who waited at least 10 months.⁷

ACL tear and surgical reconstruction rehab process

Immediately after surgery, the individual will begin their rehab toward a return to sport. As long as there was no other structure injured and/or repaired, the athlete should be able to start weight-bearing with crutches ASAP. In the first two weeks, the primary goal of rehab is to eliminate swelling, restore range of motion, and prevent muscle loss.

During the next 2-3 months, the athlete will primarily be working on building strength and maintaining range of motion. In this phase, the athlete cannot tolerate impact through the knee and will be held from running and most impact drills.

Around 12-16 weeks after surgery, the athlete can begin running. Returning to running progresses slowly, for example, starting on a treadmill and progressing to land over time. Jameis Winston was recently shown running for the first time at the 16-week post-op mark. In this video, Winston is running on an Alter-G treadmill. This device allows the individual to run at a lower body weight, thus placing less impact on the knee.

From 4-6 months, the athlete will continue to work on improving their strength and power. For example, athletes will gradually be introduced to different plyometric and agility drills such as hopping, ladder drills, hurdles, etc. Once they show good strength and ability to tolerate load on the knee, they will begin cutting and changing direction activities.

From 6-9 months, the athletes primarily work on sports and position-specific drills. As they near the nine-month mark, they may be cleared to participate in practice and eventually full-contact activities. Today’s research recommends waiting to return to sport until at least nine months post-op, as it has been shown to decrease the risk of re-injury drastically.

The return-to-run timeline can vary significantly depending on whether the athlete also had work done on the meniscus, cartilage, MCL, or other structures. For example:

- If a meniscus was trimmed, running might start by 12 weeks

- If a meniscus was repaired, running may be delayed until 16–20 weeks

- If microfracture or cartilage surgery was performed, running may be delayed even longer (5–6 months)¹⁰

| Time Line | Goals and Weight Bearing Status | Rehab |

|---|---|---|

| Post-op Weeks 1-2 | Goals: Protect surgical site. Swelling reduction. Weight Bearing Weight-bearing as tolerated with crutches and knee brace. | Restore full extension range of motion, improve flexion range of motion. Emphasize good control of the quadriceps. May begin glute, core, upper body exercises within limits. |

| Post-op Weeks 3-6 | Goals: Protect surgical site. Swelling reduction. Gradually increase weight bearing. Weight Bearing Wean off of crutches and knee brace as tolerated. | Ensure full range of motion, continue to control swelling, avoid excessive stress on the anterior knee. Continue to progress strengthening and balance exercises. May begin squats and leg press within limited range of motion. |

| Post-op Weeks 6-12 | Goals: Protect surgical site. Swelling reduction. Full weight bearing. Weight Bearing Should be full weightbearing with proper gait pattern. | Continue with previous exercises. Begin open chain exercises as tolerated (knee extensions). Progress to single leg exercises as able. May begin static and dynamic stretches. Progress balance exercises: Wobble board, standing on foam pad, single leg stance. Deep water pool walking, cycling, possible elliptical/stair stepper. |

| Post-op weeks 12-16 | Goals: Protect surgical site. Begin running and jumping. No cutting, limited change of direction activities. | Once strength is equal to at least 70% of opposite limb; begin straight line running and jumping/hopping. Likely begin some ladder drills and eccentric control exercises. Continue to progress core, balance, and strengthening exercises. |

| Post-op 4-6 months | Goals: Return to practice at 6 months. Progress position specific strength and agility Weight Bearing: Ensure single leg balance and strength is similar to non-injured leg. | Continue to progress and emphasize good control of the body during all movements. Increase challenge of balance exercises: Wobble board while tossing ball, single leg stance on foam pad while tossing ball, add cognitive task (count backwards from 100 by 3’s while balancing) Gradually progress agility and sport specific drills. Aim for return to limited practice by 6 months. |

| Post-op 6-9 months | Goals: Return to sport at 9 months. Progress position specific movements. | Continue progressing all exercises from previous phase. Pending clearance, may begin full contact practices closer toward 9 month time frame. |

| Post-op Months 9-12+ | Goals: Return to prior level of performance. | Unrestricted training. Sprinting, jumping, cutting, plyometrics, throwing, etc. |

Sam Webb, PT, DPT, SCS

References

- Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA Jr, Garrett WE Jr. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics. 2000;23(6):573–578.

- Ristić V, Ninković S, Harhaji V, Milankov M. Causes of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Med Pregl. 2010;63(7-8):541–545.

- Khair MM, Riboh JC, Solis J, et al. Return to Play Following Isolated and Combined Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: 25+ Years of Experience Treating National Football League Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(10):2325967120959004.

- Read CR, Aune KT, Cain EL Jr, Fleisig GS. Return to Play and Decreased Performance After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in National Football League Defensive Players. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(8):1815–1821.

- Arundale AJH, Capin JJ, Zarzycki R, et al. Quadriceps Strength Symmetry and Patient-Reported Function at Return to Sport after ACL Reconstruction Are Associated with Second ACL Injury. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(6):1431–1439.

- Yang J, Mann BJ, Guettler JH, et al. Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(1):58–66.

- Beischer S, Gustavsson L, Senorski EH, et al. Time to Return to Sport After ACL Reconstruction and Risk of Re-Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(1):56–66.

- Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, et al. Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1861–1876.

- Carey JL, Huffman GR, Parekh SG, et al. Performance and Return to Play in NFL Players After ACL Reconstruction. Phys Sportsmed. 2021;49(4):427–434.

- Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Minimum 10-year results after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: how the loss of normal knee motion compounds other factors related to the development of osteoarthritis after surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(3):471–480.

- Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P, et al. Return to sport and risk of ACL reinjury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(15):906–914.